Investments - Regional complementary investments in institutions, infrastructure and public services

Investments in infrastructure and public services can enhance the productivity of traditional rural economic activities, increase access to new markets, and empower the poor with assets to access these markets (Barrett et al 2011, Barbier et al 2016).

- Overview: Complementary investments in institutions, infrastructure, and public services can increase the impact of interventions to increase productivity, access to markets, as well as access to education

- Evidence map: Not much evidence exists on how complementary investments affect monetary income

- Country study: Brazil - the Bolsa Verde program provides cash transfer to forest households for adopting forest-conservation practice

- World Bank Portfolio Review: Complementary investments was the most common PRIME theme in the portfolio sample, included in 71% of the projects

Overview

Investing in roads, electricity, health care and other services have great impacts on poverty reduction through increased access to markets, productivity, educational outcomes, among others (Deininger and Okidi 2003; Chomitz 2007; Khandker et al 2013; van de Walle et al 2015 ). However, such investments are lacking given the remoteness of forest areas and the lack of tailored options for households living in forests (Barrett et al 2011, Barbier et al 2016). A principal worry with investments such as roads, for instance, is that they can contribute to deforestation by increasing access to logging, bringing in secondary settlements or attracting migrants (Angelsen 2010; Chomitz 2007). Furthermore, the responsibility for economic development in forest landscapes often falls outside the mandate of forestry agencies, making it difficult to develop appropriate policies. Earlier works and World Bank projects emphasize that forest safeguard issues are crucial to analyze to limit the negative impacts these investments could have on forest ecosystems.

Back to top

Evidence Map Results

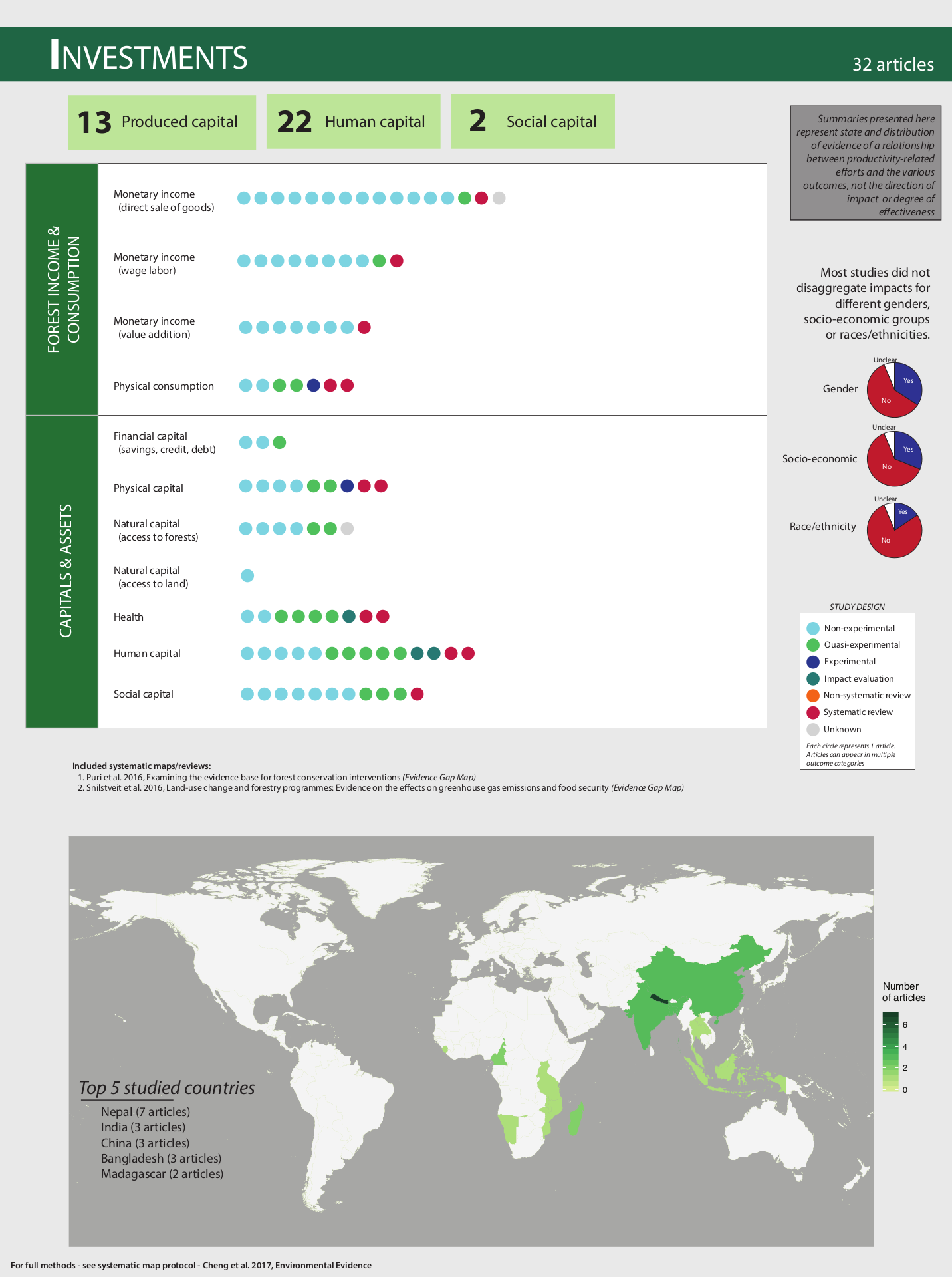

The evidence map identifies a limited number of studies analyzing investments in public services and infrastructure. The evidence map reports that 32 articles out of the 242 focused on actions linked to produced capital such as building and investing in infrastructure, in equipment and machinery, and in infrastructure for complementary activities, and linked to human and social capital such as education, health, developing institutions, among others. This assessment highlighted very little evidence on the links between these actions and monetary income through direct sales of forest goods, and social capital. These gaps are related to poor study designs to assess these links.

Back to top

Illustrative Country Study

To understand how investments may impact poverty outcomes, the analysis considered the Bolsa Verde program in Brazil. Bolsa Verde in Brazil illustrates how the national social assistance program, Bolsa Familia, was extended to include a conditionality on forest uses and on participation in trainings to receive transfers. Institutional reforms, outside the forestry sector, can empower the poor and help them benefit from social programs. Reforms that provide clarity over laws and lessen regulatory and financial constraints can help reduce barriers for market exchange and empower households to take reasonable risks. Tailored social protection programs in the form of transfers based on sustainable forest use can encourage the poor to sustainably use forest resources.

Back to top

World Bank Portfolio Review Results

The World Bank is supporting numerous projects investing in public infrastructure and services, and institutional reforms. Out of the total number of World Bank projects that met the criteria for inclusion in the portfolio analysis completed under this program (38), 27 (roughly 71 percent) contained forest investments components as defined by the PRIME framework. These projects contained additional PRIME elements, showing the synergies and complementarities that exist among the components. For example, 19 of the 27 investment projects worked on productivity; 10 had also rights components, seven markets components; and 11 ecosystems components. Geographically, the greatest number of forestry projects that contained investment components were in the Bank’s East-Asian and Pacific (EAP) and European and Central Asian (ECA) regions with seven projects each. The Sub-Sahara African (SSA) had six projects, the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) had five, and the Middle-Eastern and Northern-African and South-Asian regions had one each.

Split by

Color by