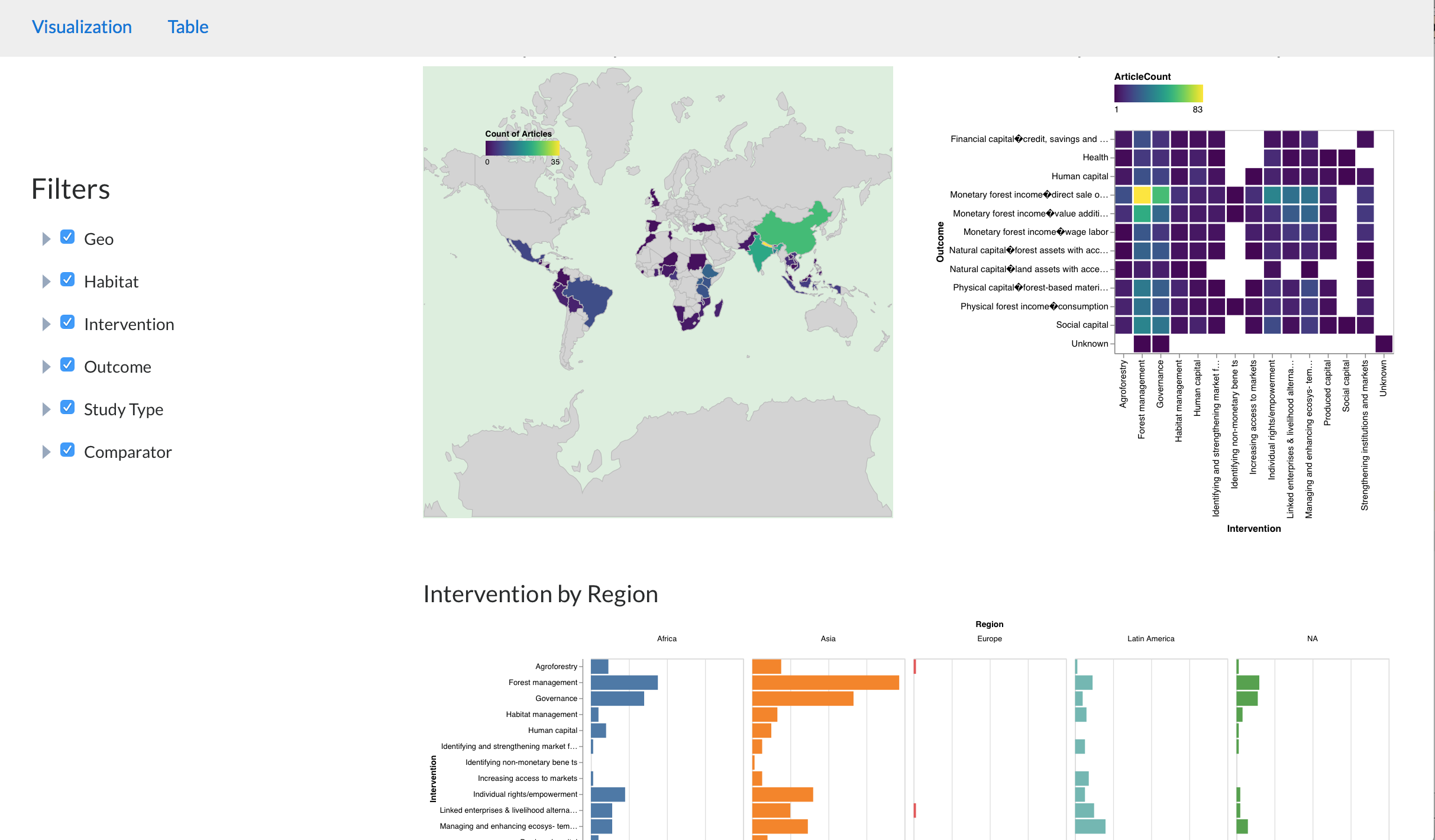

Evidence Map

While we have a working understanding of how poor people depend on forests in individual sites and countries, much of this evidence is dispersed and not easily accessible. Thus, while the importance of forest ecosystems and resources to contribute to poverty alleviation has been increasingly emphasized in international policies, conservation and development initiatives and investments—the strength of evidence to support how forests can affect poverty outcomes is still unclear.

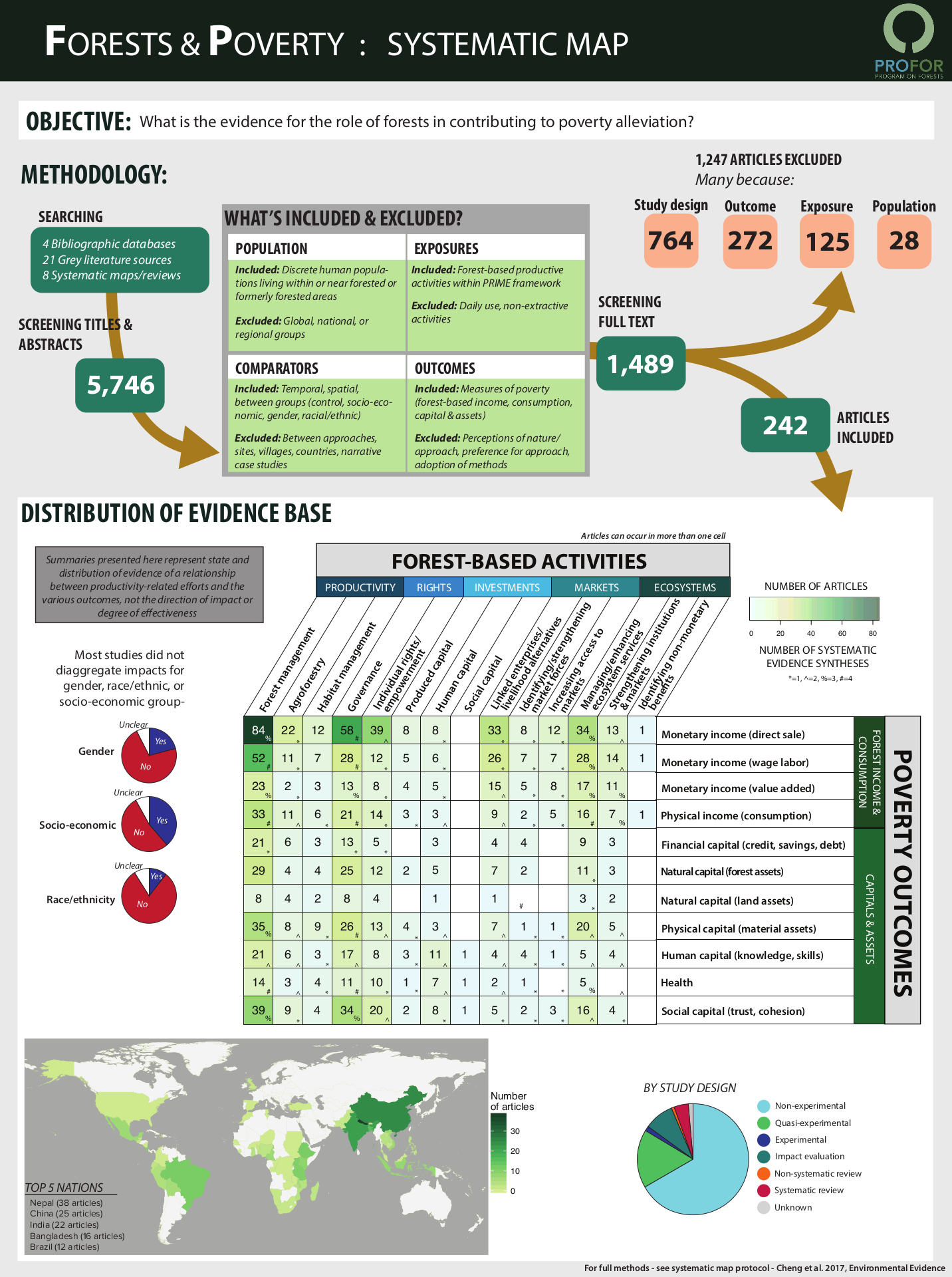

- Methodology This study takes a systematic mapping approach to scope, identify and describe studies that measure the effect of forest-based activities on poverty outcomes at local and regional scales world-wide, structured around the PRIME framework.

- Results The evidence map shows that there is a bulk of evidence on P and R , specifically forest management and governance, with regards to its impact on monetary poverty. There are significant gaps for the I,M and E pathways, as well as on impacts on produced capital, human capital or social capital, and geographical gluts on a few countries.

Methodology

Based on the protocol developed for the McKinnon et al. 2016 study, the protocol for the forest-poverty evidence map, Cheng et al. 2017 searched for empirical evidence (e.g. peer-reviewed literature, unpublished reports) in 4 bibliographic databases, 21 organizational websites, and 8 existing systematic evidence syntheses. Search results were screened for inclusion using criteria on population, exposures, comparator, outcomes, and study types.

A total of 5,746 citations had their titles and abstracts screened using the inclusion/exclusion criteria. 1,489 articles were kept for screening of the full text using the same protocol. Following this protocol, 1,247 studies were excluded due to study design (764); to non-measurable outcome (272); exposure (175); and population (29). While these studies are certainly useful to illustrate context, they are not robust tests of impact. In total, 242 studies form the evidence base.

Results

The evidence map shows that there is a bulk of evidence on P and R - specifically on forest management and governance - with regards to their impact on monetary poverty. There are significant gaps in the evidence for the I, M and E pathways, as well as for impacts on produced capital, human capital, and social capital. There are also geographical gluts of evidence on a few countries. However, research effort is not evenly distributed. Most studies examine impacts of forest management and governance regimes on changes in monetary income. In comparison - there are significant knowledge gaps on the impacts of actions that aim to improve produced capital, human capital or social capital, as well as the impact of any type of forest productive activity on natural capital (land or forest resources with access, use/sale, and exclusion rights).

The evidence map indicates a heavy geographic bias in study effort - 35% of studies were conducted in China, Nepal and India. In comparison, fewer studies focused on South America, Western Africa, North America, Oceania and Europe. Studies ranged in robustness and design, with the majority employing non-experimental designs (68%), followed by 17% quasi-experimental, 9% impact evaluations, 1% experimental studies. Although this map is not intended to provide information on what works or what is successful, this map clearly reports that the evidence base for nature-people linkages is growing despite considerable geographic, biome and study biases - with more intangible outcomes relatively little studied. However, there are some areas that are ready for further synthesis on the linkages through in-depth knowledge reviews to understand effectiveness and impacts.