poverty

Share

Related Links

A New Survey Tool Promises to Raise the Profile of Forests in National Development Agendas

Poverty-Forests Linkages Toolkit

Improving the Forests Database to Support Sustainable Forest Management

Launch of the sourcebook on national socioeconomic surveys in forestry

External Related Links

Seeing the forests and the trees

National socioeconomic surveys in forestry

Launching the sourcebook on national socioeconomic surveys in forestry

Socioeconomic Benefits of Forests

Authors/Partners

The World Bank, PROFOR, FAO

Building National-Scale Evidence on the Contribution of Forests to Household Welfare: A Forestry Module for Living Standards Measurement Surveys

CHALLENGE

Forests and trees in rural landscapes contribute to human wellbeing in a variety of ways. They provide a range of goods—from fruit to timber, fodder to firewood—and services such as pollination, hydrological regulation, and carbon sequestration that support the livelihoods of millions of people. Despite these contributions and growing recognition of the importance of landscape approaches, forests and trees often remain peripheral in wider development policy discussions. Part of the reason for this marginalization is that developing country decision-makers and planners lack the most basic information about the role and importance of the forestry sector to their national economies. Researchers, advocates, and policymakers alike increasingly recognize that a variety of assets and activities beyond agriculture underpin rural livelihoods, but the picture is incomplete in many circumstances without reliable national-scale data on the contribution of forests and trees.

Comparative research in a variety of developing country settings demonstrates the important contribution that forests can play in mitigating and reducing poverty (see, e.g., recent PROFOR and CIFOR studies). However, available evidence is primarily site-specific, and it is not clear whether results can be extrapolated to the national level. The absence of national-scale evidence on forests-poverty linkages impedes holistic understanding of the role forests can play in providing pathways out of poverty and the development of policies to achieve sustainable reductions in poverty and inequality. Lack of such data also limits capacity to establish adequate baselines, track changes over time, and assess the impact of forest-related investments on poverty.

APPROACH

This activity will help address this knowledge gap by developing a forestry module and sourcebook on its use in the context of the Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS), LSMS-Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (LSMS-ISA) and other similar national survey instruments. The objective of this activity is to mainstream the collection of national scale data on the contribution of the forestry sector to household welfare by developing and disseminating the forestry module and sourcebook. In addition to PROFOR and LSMS, this activity is a collaboration of the FAO Forestry Department, the Poverty and Environment Network (PEN), coordinated by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), the International Forestry Resources and Institutions (IFRI) research network, and the University of Copenhagen.

RESULTS

The main output of this activity is the sourcebook ‘’National socioeconomic surveys in forestry: guidance and survey modules for measuring the multiple roles of forests in household welfare and livelihoods." Field-testing was successfully carried out in Tanzania (financed by PROFOR) and Indonesia (financed by CIFOR). Based on the results of these field tests, the module and sourcebook were revised and finalized. The outputs were disseminated at the World Forestry Congress (September 2015) and at the FAO during the International Conference on Agricultural Statistics (October 2016), targeting national statistical agencies, forestry departments, and related agencies.

The original goal of this activity was to mainstream the use of national-scale data on the contribution of forests to household welfare. This work has already contributed to numerous other activities, including on understanding forests’ contribution to poverty reduction; a national survey of about 2,000 households in Turkey as part of the World Bank's dialogue with the government on forest policy; and ongoing forest and poverty work in Armenia and Georgia. In addition, the LSMS-ISA continues pushing for the adoption of the forestry module in different countries, with support from PROFOR. Engagement has started with about 8 countries, with a target of having 3-5 countries using the tool by FY19. A shorter version of the forestry module is also being promoted, so that countries can undertake initial data inquiries to assess whether there is demonstrated need for rolling out the forestry module at the national level (For instance, this was carried out as part of the 2017 Household Budget Survey in Sao Tome and Principe.)

While data is still currently being collected, initial findings from the ongoing work in Liberia clearly illustrate the heavy reliance of households on forest and wild products. These findings are expected to raise a significant amount of interest amongst stakeholders. A BBL is planned to showcase the preliminary results and implementation experience. The findings from Armenia will equip decisionmakers with evidence on the linkages between forestry reliance, energy use, and poverty, thereby enabling improvements in both environmental and social outcomes via evidence-based policy design. Similarly, further promotion of a short forestry module, following lessons learned from the Sao Tome and Principe experience, could increase the geographic coverage and frequency of data on forestry usage leading to increased knowledge and evidence for policy-making.

While it is early in the process to articulate achievements in terms of influence on policies and investments, this activity has achieved the following:

- demonstrated proof of the application concept of the forestry module in the context of national-level LSMS survey applications;

- developed and acted upon the interest of counterparts in developing these applications in new countries;

- developed and applied a community-level module of the survey design to collect, among other forest-related data, gender-specific data;

- developed a CAPI application of the survey module, to be further developed for wider dissemination.

In 2019, PROFOR provided additional support to implement the modules in the following countries:

- Liberia, as part of the Liberia National Household Forestry Survey (NHFS) implemented by the Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services (LISGIS).

- Armenia. The activity team provided sampling and questionnaire design input for a survey on forestry, poverty, and energy.

- São Tomé and Príncipe. A subset of the forestry module was included in the 2017 Household Budget Survey, intended to provide preliminary data on forest dependency and gauge the potential for future inclusion of the full module.

- Turkey

- Georgia

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Author : The World Bank, PROFOR, FAO

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

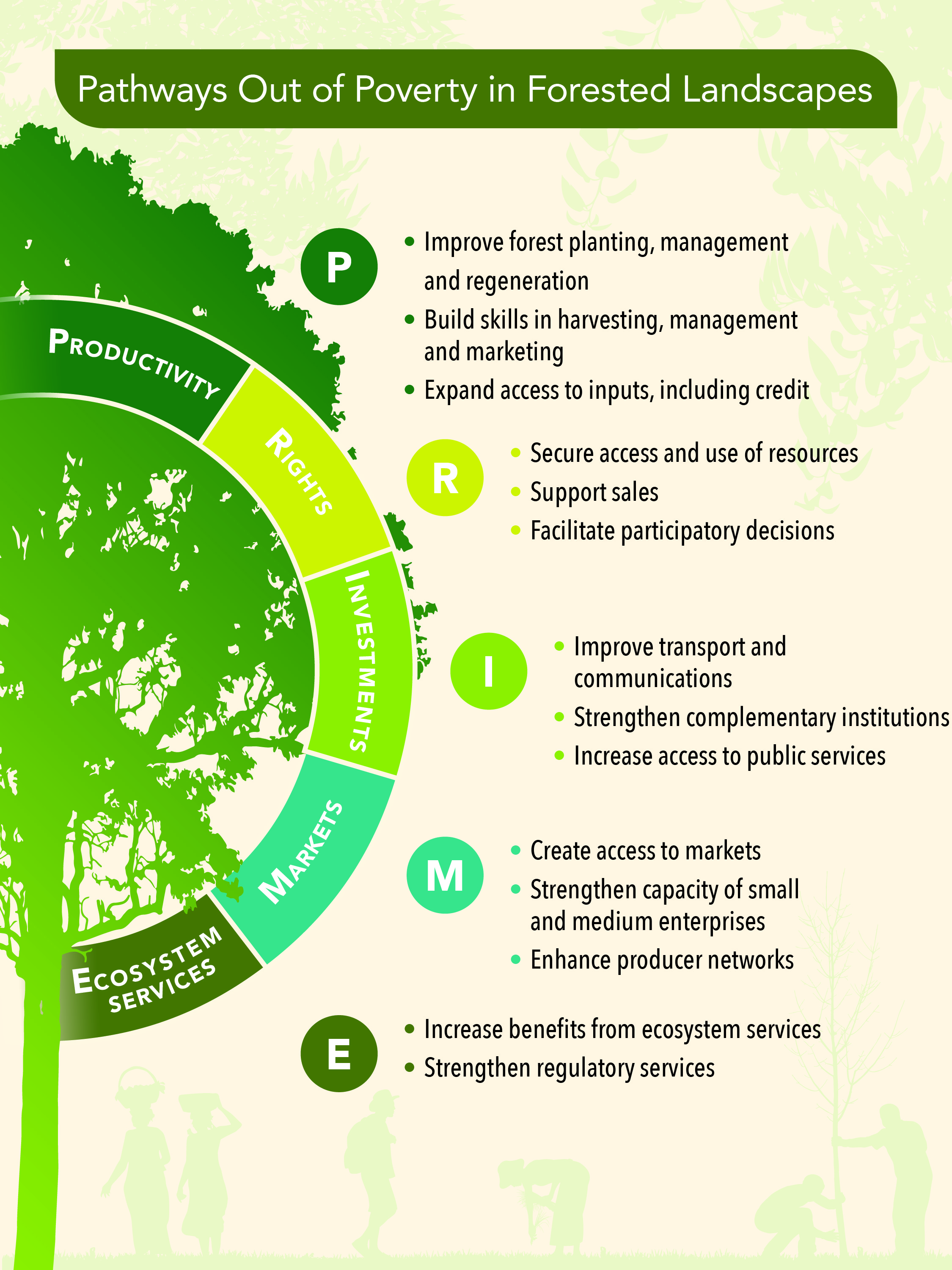

P.R.I.M.E. - Pathways toward Prosperity

By: Priya Shyamsundar, Stefanie Onder, Sofia Ahlroth and Patti Kristjanson

Five broad pathways can help launch the forest-dependent poor onto a sustainable path toward prosperity. These pathways, referred to as PRIME, identify economic development strategies and build on the premise that forests themselves will remain intact.

PRODUCTIVITY: Growth in labor and resource productivity (P) is integral to economic development. In forested landscapes, labor productivity can be improved by enhancing individual and community skills in sustainable forest management. Resource productivity can be improved through the infusion of capital (for instance, portable sawmills), forest fire and pest management or tree plantations. Associated technologies, policies, and capacity strengthening activities need to meet the requirements of women, indigenous people and other marginalized households to ensure that the poorest benefit.

RIGHTS: Wealth accumulation is an essential pathway out of poverty. One strategy is to increase the wealth of the poor by strengthening their rights (R) over natural capital. A large literature and local environmental movements point to the importance of community rights to use and sell forest resources in poverty reduction. Within forested communities, empowering women and other marginalized individuals to have tenure rights and decision-making power is particularly important.

INVESTMENTS: Poverty reduction in forested landscapes will not be possible without investments (I) in complementary institutions and public services. Forest-related pathways to prosperity are only likely if the poor also have inclusive and affordable access to complementary public services such as education, health, agricultural extension, transportation and mobile phone access. The role of gender-responsive institutional arrangements in providing information, enabling local level innovation and offering insurance from down-side risks will be important.

MARKETS: Income generation and diversification require strengthening small and medium timber and non-timber enterprises and increasing their access to markets (M). Markets for a small number of high-value non-timber forest products (e.g. Brazil or Shea nuts) offer one pathway that is likely to be more beneficial to women, for example. Timber certification and export markets for timber offer an alternate broader approach. This pathway may need careful designing to be responsive to the preferences of women, indigenous households and youths, and, conservation requirements.

ECOSYSTEMS: Ecosystems and their hidden services (E) are integral to prosperity. Over the last decades, policy instruments such as eco-tourism, payments for ecosystem services and carbon markets have proven to be useful mechanisms to regulate ecosystem services and their benefits. It is important to channel this demand for ecosystem services into monetary and non-monetary support for the poor, and, women within poor households.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Trees and forests are key to fighting climate change and poverty. So are women

According to WRI's ‘Global Forest Watch’, from 2001 to 2017, 337 million hectares of tropical tree cover was lost globally – an area the size of India.

So, we appear to be losing the battle, if not the war, against tropical deforestation, and missing a key opportunity to tackle climate change (if tropical deforestation were a country, it would rank 3rd in emissions) and reduce poverty. A key question, then, is what can forest sector investors, governments and other actors do differently to reverse these alarming trends?

One way to speed up our efforts is to proactively include the role of women in the design of forest landscape restoration and conservation efforts. It is only recently that people developing forest restoration programs have thought about their impact on women, and the risks of failure that come with ignoring women’s needs and potential contributions.

We know that men and women access, use and manage forests differently, with differing knowledge and roles in the management of forests and use of forest resources. Although there is still limited evidence of the magnitude and breadth of impacts achieved by implementing gender-responsive policies and practices in the forest sector, we are starting to see more evidence that taking into account gender differences could lead to behavioral changes that increase tree cover and improve the livelihoods of the poor.

Considering gender differences in the use of, access to, and benefits from forest landscapes has led to more fair and effective design of interventions and institutional arrangements that have maximized program results and successes in addressing deforestation in many countries.

For example, in Brazil, supporting women’s non-timber forest product (NTFP) microenterprise groups resulted in increased incomes and empowerment, as well as a reduction in deforestation. In India and Nepal, increasing women’s participation in community forest management groups led to improved forest conservation and enhanced livelihoods. In Uganda, a gender-transformative ‘adaptive collaborative management’ approach for communities resulted in tens of thousands of trees being planted by women for the first time both on-farm and in forest reserves, improved food security, and the election of 50% women leaders in forest management groups. In Kenya, the Green Belt Movement launched by Nobel laureate Wangari Maathai, with women’s empowerment at its core, has planted over 51 million trees.

The thought of designing and implementing gender-transformative landscape initiatives of any type (projects, programs, policies, capacity strengthening efforts, etc.) can be daunting for development practitioners or decision makers without experience considering gender. It doesn’t have to be.

A recently released paper from the World Bank’s Program on Forests (PROFOR) examines the types of gender inequalities that exist in forest landscapes, and the gender considerations or actions that many countries are taking to address these gaps. It reviews and synthesizes a wide range of World Bank and partner projects and forest sector investments in different regions.

The PROFOR paper aims to stimulate greater understanding of potential opportunities by providing suggestions for gender-responsive actions that developers and leaders of forest projects, programs and policies can consider. Depending on which forest actor you are, applying and tailoring these suggestions to your context specific circumstances can ensure more effective and equitable impacts:

- A developer or investor in forest landscape projects can consider establishing performance-based contracts with joint spousal signatures for planting and protecting trees on farms, as well as near and inside forests, or including budget line items for gender-targeted NTFP activities.

- Governments, particularly forest-related agencies, can train forest personnel in the collection of sex-disaggregated data and inclusive, participatory engagement and forest landscape management planning processes, or facilitating registration for forest-related programs in easily accessible spaces where women already go (e.g. schools, health care centers).

- Investors, development agencies and private sector actors can find ways in which to make direct payments to women (e.g. via cellphone) for forest restoration and agroforestry activities or supporting rural women’s leadership capacity and strengthening activities.

PROFOR’s paper, along with a guidance note for project designers, provide many more examples of how gender analysis and actions can contribute in forest landscapes and of how this research is already being applied on the ground. For example, the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) includes several countries that are using this tool to design REDD+ readiness and large-scale programs that ensure women are partners in the planning, operation, and deployment of climate finance.

The bottom line is that greater investment in forest landscapes and agroforestry will be critical in efforts to address climate change and rural poverty challenges in many countries. The success of these investments will be enhanced by considering gender-responsive activities and actions when designing and implementing forest landscape projects and programs.

This blog by Patti Kristjanson was originally published by The World Bank

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Food and forests: We can have them both

Agriculture provides most of the world’s food. It also contributes the most to global deforestation.![]() This does not mean, however, that we need to choose between feeding a rapidly growing population and protecting the forests that are so essential to our wellbeing.

This does not mean, however, that we need to choose between feeding a rapidly growing population and protecting the forests that are so essential to our wellbeing.

While many countries have first depleted their forests before seeing a rebound in tree cover, this “business-as-usual” scenario is not inevitable.![]() But changing it does require a paradigm shift. In part, it means redefining what “successful” pathways to sustainable development look like, so that they resonate with local leaders and reflect local realities – and thus gain political support. In addition, transitioning away from the status quo depends on forming new and creative partnerships between companies, communities, governments, and investors.

But changing it does require a paradigm shift. In part, it means redefining what “successful” pathways to sustainable development look like, so that they resonate with local leaders and reflect local realities – and thus gain political support. In addition, transitioning away from the status quo depends on forming new and creative partnerships between companies, communities, governments, and investors.

How to bring about this new food-and-forest paradigm? An ongoing study - funded by the Program on Forests (PROFOR) and led by the World Bank's Agriculture and Environment Global Practices along with experts from many agricultural and environmental organizations - is trying to find concrete answers. The team is focusing on six agricultural commodities: three that are heavily implicated in deforestation activities (palm oil, soy and beef), and three that could include planting trees in their cultivation (cocoa, coffee and shea butter). In an initial synthesis study, the researchers draw out some key lessons for removing deforestation from agricultural supply chains sooner rather than later, and for increasing the planting of trees in agricultural lands. Here are just six of their takeaways:

- Success starts with the farmer. There are many agricultural practices which, if implemented at scale, can benefit crop yields while slowing deforestation or increasing tree cover. Not only must farmers be fully equipped with this information, but they should be consulted and supported in making the transition to sustainable production systems.

- It is important to recognize and reward innovators. A system based entirely on punishing those who contribute to deforestation is unlikely to be effective in the long run. A more promising approach is to reward farmers who use creative, forest-friendly practices, while widely promoting the monetary and ecosystem benefits of these methods.

- Corporations’ sustainability pledges are important but not sufficient. A new and promising trend is the emergence of technical, commercial, and financial partnerships between companies, farmers, communities, and regional authorities.

- Government policies and programs need to be updated. In many cases, existing regulations prevent farmers from harvesting and marketing trees, deterring them from planting trees in agricultural landscapes. Ministries of agriculture and of environment need to work together to revise these legal frameworks so that farmers can sustainably grow and harvest trees on their lands.

- Regional action is critical. Efforts to combat deforestation in the agricultural sector sometimes fail because supply chains transcend national boundaries. Large-scale transformation is possible, but it needs to be backed-up by multi-stakeholder processes that lay out a shared vision for a region.

- The costs of forest loss need to be communicated more clearly. Forest conservation is often viewed through the lens of foregone agricultural profits. Governments should do a better job of communicating why forests are so crucial. For instance, improved management of shea trees in Sahelian countries could strengthen economic returns and ecological stability, with possible knock-on benefits like sustained income generation, jobs for women and youth, and lower incidence of conflict and migration induced by poor access to natural resources.

Initial findings from the synthesis study, “Leveraging agricultural value chains to enhance tropical tree cover and slow deforestation (LEAVES),” will be shared at the Global Landscapes Forum (GLF): The Investment Case in Washington, D.C. on May 30th. Its authors hope to start building momentum for their new approach to productive and sustainable agriculture.

“Although the private sector has been the main driver behind sustainability initiatives like Brazil’s Soy Moratorium and Cattle Agreement, support from the World Bank was instrumental,” said Dora Nsuwa Cudjoe, Senior Environmental Specialist, and Co-Task Team Leader of the LEAVES knowledge product at the World Bank. “The Bank can show the same level of engagement in the agroforestry commodities like coffee, cocoa, and shea, to help scale up private sector efforts. The opportunity is here.”

Photo: Josephhunwick.com

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Share

Five reasons to celebrate forests

Trees may not seem like anything exceptional, but they perform a myriad of services that we rarely recognize.![]() From making cities cleaner and cooler, to providing economic lifelines to millions of people, trees and forests are central to our environment as we know it.

From making cities cleaner and cooler, to providing economic lifelines to millions of people, trees and forests are central to our environment as we know it.

Unfortunately, global forest loss is at an all-time high, and unless we act soon, we risk unprecedented (and possibly irreversible) ecological changes.

It’s time to stop taking forests for granted. On this International Day of Forests, take a minute to enjoy the trees in your environment and to appreciate just how important forests are around the world. Here are five reasons to celebrate forests:![]()

1. Higher incomes, more resilient communities

Across the world, trees and forests provide benefits to around 1.3 billion people, including as a source of food, timber, fodder, fuel, and habitat for biodiversity. A PROFOR study in five African countries found that trees on farms make up as much as 17 percent of rural households’ gross annual income. And in Lao PDR, research shows that villages with greater access to forests are less sensitive to climate change because they can to turn to forests for resources during hard times. Ongoing PROFOR work is exploring the ways in which forests might also provide pathways out of poverty.

2. More jobs

Global demand for wood is growing rapidly. By investing in the forest sector, countries can create good jobs, support local artisanship, and formalize timber markets so that wood is sustainably harvested, and natural forests are protected. In Colombia, a PROFOR-supported study estimated that the forestry sector could reach a production value of over $4 billion and create 35,000 permanent jobs in forest plantations and industries. Another study in the Congo Basin found that urban timber markets already generate USD $15 million annually and employ at least 5,000 people.

3. More productive and cost-effective agriculture

Far from crowding out crops, trees can often improve agricultural yields by improving soil quality and regular water availability. PROFOR research in Malawi found that, instead of subsidizing fertilizer, the government could save about $71 million every year by encouraging farmers to grow trees in their maize fields. And agroforestry is not just an option for small farms; private enterprises like Fazenda da Toca in São Paulo are proving that large-scale agroforestry is viable and cost-effective.

4. Lower risk of natural disasters

Forests are a critical regulating force for our environment. A PROFOR study in the Philippines showed that higher forest cover ensures a more reliable water supply during the driest months of the years, while reducing the volume of floodwater during the wettest months. Forests also stabilize hillsides by decreasing the risk of soil erosion, helping to reduce the impacts of landslides and other natural disasters. Compared to man-made structures like dams and, maintaining forests is a much more cost-effective way to provide these benefits.

5. A more stable climate

Not only do trees help to cool our immediate surroundings, but by storing carbon they reduce the impacts of climate change. Unless, of course, we fail to protect them. An ongoing PROFOR activity finds that the southern Amazon Forest is under such stress from droughts and fires that it might soon become a net emitter of carbon dioxide (CO2). The good news is that it’s not too late to start restoring a billion hectares of degraded forests worldwide. A recent report, funded by the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) and PROFOR, estimates that investing in forest restoration and increased use of wood products in six countries could result in more than 150 million tons of CO2 equivalent being sequestered.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

In the Philippines, forest investments offer significant returns

It’s well understood that forests are worth more than the sum of their trees. As an ecosystem, forests provide an astonishing array of benefits, from the more obvious ones like timber, fruits and nuts, to the intangible ones like maintaining reliable flows of clean water. But how much are these benefits actually worth? And are forests really so much better at providing these services than, say, human-engineered technology?

According to a new study in the Philippines, reforestation and forest rehabilitation may truly be the most cost-effective option for producing valuable ecosystem services that many people depend on – especially given the uncertainties brought on by climate change.

With funding from the Program on Forests (PROFOR) and technical support from the World Bank, the Government of the Philippines studied three different areas to assess the value of certain “invisible” forest-derived benefits. The research found that healthy forests help reduce risks to climate variability by providing high-quality ecosystem services that contribute to more resilient communities.

For instance, the study showed that in the Upper Marikina River Basin – a degraded watershed upstream from Manila, where most inhabitants live below the poverty line - higher forest cover results in 149 to 167 percent higher water yields during the driest months of the year, ensuring a more reliable water supply during times of scarcity. Meanwhile, during the wettest months, forests can reduce the volume of floodwater in the watershed by 27 to 47 percent. Forests also stabilize hillsides and mountainsides in the region by decreasing the risk of soil erosion by 68 to 99 percent per hectare – helping reduce the impacts of natural hazards like flooding and landslides.

“These services are worth billions of pesos,” emphasized Eugene Soyosa, Economist at the Philippines Forest Management Bureau. “Maintaining forests has a much lower cost than if you would build check dams or other erosion control measures.”

Crucially from a sustainable development perspective, forest ecosystem services are integral to the well-being of poor communities in the Philippines. According to the findings at one pilot site, people obtain about 7 percent of their annual cash income from selling forest resources like bamboo, charcoal, fish, and bush meat.

“Poor households are very dependent on forests, especially for water provisioning services” said Maurice Andres Rawlins, Natural Resource Management Specialist at the World Bank and a lead author of the study. “If these services were lost and people had to pay for them, it could certainly set back poverty reduction gains.”

“In the pilot site of Upper Marikina, forests have been degraded for charcoal-making and the water supply is decreasing; at other sites, the siltation is very pronounced,” explained Soyosa. “When we first talked to communities, they perceive the idea of ecosystem services as too technical. But as the conversation moves on, it turns out that they know a lot about these benefits, and are being heavily impacted by the loss.”

Forest ecosystem services become more important as the impacts of climate change intensify. The Philippines - being an archipelagic country that is naturally vulnerable to typhoons, earthquakes and storm surges– also ranks among the top 5 countries most affected by climate change. According to projections, all areas of the Philippines will get warmer, contributing to more frequent extreme weather events. Dry seasons will become drier, and wet seasons wetter. This study confirms that forests provide services that make communities more resilient to climate change shocks, including acting as a safety net against poverty.

The Government of the Philippines is already trying to reverse trends of severe deforestation and forest degradation across the country, and has been working on the valuation of ecosystem services with help from the World Bank-led Wealth Accounting and the Valuation of Ecosystem Services (WAVES) Global Partnership. This work is motivated by the recognition that documenting economic values of forest resources can help make forest investments more attractive, and thus improve the livelihoods of poor upland communities.

“The Philippines is committed to regreening,” said Rawlins. “They don’t want to just plant forests where there are none, but to undertake more strategic thinking about which areas to prioritize, and what kind of trees to plant. That’s where measuring specific ecosystem services results is so important. The question now is, ‘How do we mainstream these processes into planning?’ The ability of the government to include this work in their regular processes is the true sign of success.”

Findings of the study are intended to guide the Philippines’ National Greening Program by including forest ecosystem services into land use planning processes. Results have also shaped the indicators in the country’s Forest Investment Road Map (FIRM), which is the government’s strategy for accelerating sustainable economic growth in the wood industry through private sector investment. The FIRM, in turn, is consistent with the Philippines Master Plan for Climate Change-Resilient Forestry Development, which aims to promote the development of forest plantations and increase the participation of the private sector, local government units, and organized upland communities.

“In the Philippines we have not yet established a national database on forest ecosystem services in terms of inputs into policies and programs,” said Larlyn Faith Aggabao, Senior Forest Management Specialist at the Forest Management Bureau. “This study is a useful start to institutionalizing and formulating a coordinated effort among different agencies for data collection, data sharing, and analysis. This information would provide significant inputs to forestry plans because there are trade-offs to any policy, and these need to be managed.”

(Photo credit: Gordon Bernard Ramos Ignacio)

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Ecological restoration, critical for poverty reduction

By Joaquim Levy, World Bank Group Managing Director and Chief Financial Officer

Why is ecological restoration so critical to the World Bank’s mission of reducing poverty and boosting shared prosperity? Quite simply, because environmental degradation is devastating to the most vulnerable communities![]() and perpetuates poverty around the world.

and perpetuates poverty around the world.

Some 42 percent of the world’s poorest live on land that is classified as degraded. The situation becomes worse every year, as 24 billion tons of fertile soil are eroded, and drought threatens to turn 12 million hectares of land into desert.

The costs associated with environmental degradation can be compared to the impacts of a natural disaster.![]() In Indonesia, for example, a few months of peat fires created more economic damage than the Tsunami in Aceh.

In Indonesia, for example, a few months of peat fires created more economic damage than the Tsunami in Aceh.

Thankfully, there is still time to reverse this type of harm. Worldwide, about two billion hectares of degraded forest land could be restored, creating functional, productive ecosystems that can boost sustainable development. Governments and other stakeholders are motivated to make this happen – nothing was clearer from my participation in the 7th World Conference on Ecological Restoration, last week in Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil.

So how do we take the next step and make large-scale environmental restoration a reality? We need to keep a few key principles in mind:

First, we need to think of a new forest economy. Environmental restoration at the scale we need requires going beyond conservation.![]() It means integrating timber and food production, as well as energy and disaster risk management, particularly when it comes to water resources. We need to look at countries like Austria, Germany and South Korea, which have built entire rural economies on high-tech forest value chains that are not only highly productive, but also ecologically meaningful. The World Bank has supported this approach in several places, including China, where an erosion control project returned the devastated Loess Plateau to a thriving landscape that supports sustainable agriculture and the livelihoods of 2.5 million people.

It means integrating timber and food production, as well as energy and disaster risk management, particularly when it comes to water resources. We need to look at countries like Austria, Germany and South Korea, which have built entire rural economies on high-tech forest value chains that are not only highly productive, but also ecologically meaningful. The World Bank has supported this approach in several places, including China, where an erosion control project returned the devastated Loess Plateau to a thriving landscape that supports sustainable agriculture and the livelihoods of 2.5 million people.

Second, we need to find efficient, low-cost restoration solutions that can be brought to scale. This means investing in rigorously tested scientific methods, because we cannot afford to make large-scale mistakes. It also requires customized solutions capable of meeting the various restoration challenges, from evaluating whether native species are always the best choice, to considering a range of time horizons. Brazil’s commercial restoration sector is a leader in this field, with cooperative, inter-company research contributing to the success of the commercial plantation sector.

Third, we need to ensure legal rights for forests. There can be no thriving forest economy without sound tenure rights, including for Indigenous and traditional peoples. Some countries are making progress on this front. In Nicaragua, for instance, all ancestral territories of Indigenous Peoples in the Caribbean Region are now mapped and titled thanks to legal, policy, and institutional reforms that began 15 years ago, with World Bank support.

Fourth, we need to better understand the value of our forest services. Adopting natural wealth accounting that values assets such as land, forests, and minerals as a companion to GDP would help state the economic cost of degradation and the benefits of restoration. Armed with such information, Ministers of Finance may become restoration champions, and governments would have the tools to develop a forest-smart approach that works across economic sectors and at the right scale. Consider the case of Costa Rica: by establishing forest accounts, the government documented that forests contributed close to 10 times more to GDP than was previously thought.

The last missing link is financing. We need to consider all levels of financing, starting with small and medium-sized enterprises. Forest development and integrated agriculture need to be made attractive to entrepreneurs![]() , including women and the young.

, including women and the young.

In addition, tax and transfer systems must recognize the importance of environmental services. Providing strong governance and guidance on the use of environment compensation fees, such as Brazil’s “compensaçao ambiental,” ought to be a priority. Local solutions need to be discussed everywhere, along with international incentive systems.

Finally, when adequately-funded and accountable research starts to generate the right technology, sizeable financial resources will flow to restoration.

To recap: ecosystem restoration is critical for sustainable development and poverty alleviation![]() ; there are significant opportunities for putting these approaches into practice; and we have a solid understanding of the core principles that contribute to successful restoration efforts.

; there are significant opportunities for putting these approaches into practice; and we have a solid understanding of the core principles that contribute to successful restoration efforts.

At the World Bank Group, we stand ready to support countries’ restoration efforts through our financing tools and partnership programs like the Program on Forests (PROFOR). Together, our efforts can have a transformative impact on improving the lives of the poorest and benefitting the environment.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

New tool to deliver swifter, better data on forests-poverty linkages

Q: What's better than having accurate, detailed and widely representative data?

A: Data that is accurate, detailed, widely representative - and frequent.

In fact, frequent data allows us to create not just a snapshot of our world, but to tease out complex patterns developing over time, and to make predictions into the future. This kind of information has never been more important for forests, which are at the heart of many sustainable development efforts, from the Paris Climate Agreement to the Sustainable Development Goals.

We know that forest resources are crucial to some 1.3 billion people worldwide, and that forests store over a billion tons of carbon. But we also know that climate change, demographics, migration, economic trends, and many other factors have significant impacts on forests and the people who, directly or indirectly, rely on them.

Consequently, building an in-depth understanding of how poor communities depend on forest resources is critical to developing policies and programs that simultaneously enhance those benefits and conserve habitats. To go about this, the World Bank’s multi-donor Program on Forests (PROFOR) previously partnered with a number of organizations to produce a “Forestry Sourcebook,” a survey tool aimed at collecting detailed level data about how people use forest resources.

The one challenge of the sourcebook approach, however, is that its implementation relies on the rollout of national-level household surveys – a necessarily complex and costly undertaking that occurs every three years as part of the Living Standards Measurement Survey (LSMS). So in order to complement the information gathered through the sourcebook's forestry module, PROFOR is also funding the development of a quicker, cheaper tool: the Forest Survey of Wellbeing via Instant and Frequent Tracking (Forest-SWIFT). It combines statistical methods with in-person interviews to provide robust measures of forest dependence and poverty, and uses tablets or smart phones so that data can then be rapidly collated and analyzed.

“Compared to the LSMS, Forest-SWIFT can be carried out in less time in the field and at a fraction of the cost, since the questionnaire can be done in less than 30 minutes,” explained Emilie Perge, a World Bank Economist leading the project. “The ultimate outcome of the Forest-SWIFT is to inform how forest projects are implemented, how to target beneficiaries, and how to monitor outcomes.”

So far, the Forest-SWIFT methodology has been piloted in Turkey, where Perge worked with Senior Environmental Economist Craig Meisner to model poverty and forest reliance. Some 7 million people – 40 percent of the rural population - live in Turkey's forest villages, and while they depend heavily on forests for income, they also suffer from below-average poverty rates.

“Forest villagers are declining in numbers due to large-scale urbanization in Turkey,” Meisner said. “We undertook a nationally representative survey of forest villages and found that forestry is a critical source of income for the poorest households, but is still a low-productivity activity. The results highlight the potential of forest cooperatives as a helpful tool for stemming migration, as well as the need to boost productivity and jobs in the forestry sector.”

Findings from the Turkey activity have been aggregated into a Forest Policy Note for Turkey's national forestry agency, and will be used to revise the country's new five-year forest strategy.

There are also plans to implement the Forest-SWIFT in Argentina, as part of an activity led by Senior Natural Resources Management Specialist Peter Jipp. The activity will focus on the Chaco Eco-region, where poverty and deforestation rates are among the highest in the country. With 1.5 million hectares of forested land being converted to agriculture between 2006 and 2011, communities are losing valuable ecosystem services and sources of income.

“Evidence from other countries suggests that the poor rely on forests for 25-35 percent of their income, but there are no such statistics for Argentina,” said Jipp. “This study will help fill that knowledge gap. Communities of indigenous and criollo origin will be a particular focus, as 70 percent of them live below the poverty line. The Forest-SWIFT will also support an impact evaluation of Argentina's Forest Fund, to assess how successful it was in preventing forest loss and land-use change.”

In addition, there is the possibility of applying the tool to forest and poverty data from Mozambique, and hopefully to other interested countries as well.

“There are so many cash and non-cash benefits that poor communities get from forests,” noted Werner Kornexl, Senior Environmental Specialist and PROFOR Manager. “This data can help us understand the real value of forests and improve policies to support poverty reduction efforts while also find new solutions for a more prosperous forest-based industry.”

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Resolving forest tenure is key to promoting sustainable development and human rights

Imagine that you’re standing in a forest. Far below your feet, there could be valuable oil or mineral deposits that are probably owned by a national government. The soil that you’re standing on belongs to whoever holds a title to that land – an individual, a corporation, a community, or a local or federal authority. But who owns the trees?

In Latin America the answer to that question is, increasingly, indigenous peoples and local communities. “There was a spike in the trend of transferring access and control of forest resources from governments to indigenous communities,” said Gerardo Segura Warnholtz, Sr. Natural Resources Management Specialist and author of a new, PROFOR-supported book on forest tenure regimes in Latin America. “These changes were driven by governments realizing that they don’t have the capacity to adequately manage forests, and by the demands of local communities advocating for forest rights.”

Worldwide, secure land and forest tenure is gaining recognition as a key component of many sustainable development efforts, from promoting economic growth, to conserving biodiversity and reducing carbon emissions, to protecting human rights. “Tenure is seen more and more as a common denominator across several sectors, including agriculture, rural poverty, and climate change initiatives like REDD+ that depend on clarifying ownership of carbon,” Segura said.

Encouragingly, studies have shown that, where communities have strong forest rights and sufficient government support, deforestation rates (and associated carbon emissions) are much lower compared to areas outside community forests. This is crucial from a climate change perspective, as an estimated 25 percent of all carbon stored aboveground in tropical forests is being collectively managed by indigenous people and local communities.

However, many indigenous peoples are part of tenure systems that lack sufficient legal standing, and individuals may face severe challenges in exercising political power. “We are talking about basic human rights,” Segura emphasized. “It’s especially important to remember that most forested lands are, or have been, inhabited by local communities, many of whom have been marginalized.”

Consequently, Latin America’s recent efforts to reform forest tenure regimes are a crucial step in the right direction. But do they go far enough? Segura and his research team used the “bundle of rights” concept to analyze 10 tenure systems in six different Latin American countries: Argentina, Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Peru. Of the 10 systems, the team found that seven meet all of the requirements for a full bundle of rights, meaning that communities on these lands were entitled to access forests and exclude others from doing so; use and manage forest resources at their discretion; challenge a government’s decision to infringe on these rights; and hold these rights indefinitely.

That said, many countries have yet to fully implement these legal frameworks. In Peru, for instance, land titling initiatives have moved slowly, and have concentrated on the Amazon region, where local and national activism efforts have been the strongest. Across all of the countries analyzed, limited institutional, technical and financial capacity poses obstacles to comprehensive forest tenure reform.

In addition, three regimes in Segura’s analysis maintain some restrictions on the bundle of rights, while El Salvador has yet to reestablish collective land ownership since it was abolished in the late 1800s. The country also only recognized the legal status of indigenous minorities in 2014. “El Salvador is the outlier in this study, but in a general way it acts as a good illustration of what happens when we don’t act,” explained Segura. “El Salvador lost most of its forest a long time ago, and its agricultural economy is on the verge of collapse. We are seeing so many threats to forests around the world - if we’re not more careful about forest management, the consequences could be devastating.”

Segura’s hopes that, with the publication of his new book and ongoing PROFOR work to consolidate and promote understanding and best practices around forest tenure reform, governments and development institutions will be convinced that undertaking forest tenure reform is well worth the risk.

“This topic is seen as so complicated, risky and contagious,” he said. “How can we de-risk it? We need to translate the knowledge we have into tools that are directly useful to practitioners. Governments need to keep devolving rights to communities, as well as establishing and enforcing management rules in a transparent and inclusive way. If we can achieve that, there will be positive outcomes for conservation and for development.”

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024

Understanding the Role of Forests in Supporting Livelihoods and Climate Resilience (and Twin Goals) in the Philippines

CHALLENGE

Tremendous progress has been made in reducing poverty over the past three decades. Nonetheless, more than 1 billion people worldwide still live in destitution. In addition, rising prosperity in many countries is accompanied by social exclusion and increasing inequality. The post-2015 Development Agenda has thus made reducing poverty its priority. The new World Bank strategy reinforces this objective, aiming to end extreme poverty in a generation and to promote shared prosperity for the bottom 40 percent. These goals will only be achieved if development is managed in an environmentally, socially, and fiscally sustainable manner.

The challenge for development is that the poor are often highly dependent on natural resources, such as forests. Although forests provide ecosystem services and safety nets for the livelihoods of the poor, forests are facing significant pressures from the range of sectors that are critical for economic growth, such as agriculture, transport and energy. Therefore, if sustainably managed, forests could play a significant role in achieving the twin goals of reducing poverty and building climate resilience. However, our understanding of this dual forest-poverty relationship is limited, which this study seeks to address..

APPROACH

This study focuses on the Philippines where, similar to many tropical countries, extensive deforestation and forest degradation have taken place over the last century due to logging, fires and other human disturbances, which are further aggravated by climate change. The country’s total forest cover has declined to merely 6.9 million hectares, or 23% of the total land area.

This study builds on the three primary roles that environmental income plays in supporting rural livelihoods: (i) supporting current consumption; (ii) providing safety nets to smooth income shocks or offset seasonal shortfalls, as well as impacts of climate change; and (iii) providing the opportunity to accumulate assets and exit poverty. Each of these roles is examined further in how they depend on and impact the ecosystem services provided by forests (including the impacts of climate change), and how they can help reduce extreme poverty and promote shared prosperity for the bottom 40%. Three case study sites were examined: the Upper Marikina RIver Basin Protected Landscape (UMRBPL), the Libmanan-Pulantuna Watershed (LPW), and the Umayam, Minor and Agusan Marsh Sub-basin (UMAM).

RESULTS

- Higher forest cover generates higher water yields during the driest months of the year.

- If the water regulating services provided by forests were to be replaced by delivered water, the expected costs would be USD 419-1,064 per household per year, depending on the study site. These costs will be prohibitive to most households in the study sites as the majority subsist below the poverty line.

- Compared to a “no forest” scenario, forest reduce the volume of floodwater by 27% to 47% during the three wettest months of the year. Forests on steep slopes (>30%) help mitigate the risk of erosion by 68% to 99% per hectare, and have the potential to reduce annual sediment outflows from watersheds by 7 to 100 times compared to bare soil.

- Replacing erosion and sediment control services with manmade control measures will cost billions of pesos. Reforestation is a lower-cost alternative to securing erosion regulation ecosystem services over the medium term.

- Water was cited by poor upland communities as the most important subsistence benefit from the forest, which they use for domestic purposes and, in some instances, for irrigation.

- Upland communities in UMRBPL reported that about 7% of their annual cash income comes from the sale of forest resources like bamboo products, charcoal, fish, and bush meat. Approximately 40% of their annual income comes from the sale of farm produce grown on forested land.

- Forests also provide fuelwood and wood for charcoal, which supplies most of the communities’ energy needs.

- Poorer households in upland communities rely more on forest resources for income and subsistence

The study concludes with a list of recommendations for landscape planning and forest management:

- Incorporate ecosystem service modeling and valuation, forest use analysis and scenarios in forest land use planning and forest management.

- Improve access of upland and forest dwelling communities to forest resources.

- Enhance the value of forest assets by internalizing non-market values and adding value to the existing sources of income.

For stories and updates on related activities, follow us on twitter and facebook , or subscribe to our mailing list for regular updates.

Last Updated : 06-16-2024