Markets - Improving Market Access

Creating, easing, and encouraging access to markets through small and medium enterprises (SMEs), access to credit and technologies, and networks of enterprises are well-established conduits for jobs and wealth generation.

- Overview: Access to markets is a hurdle for households trying to go beyond own-use production of timber and non-timber forest products

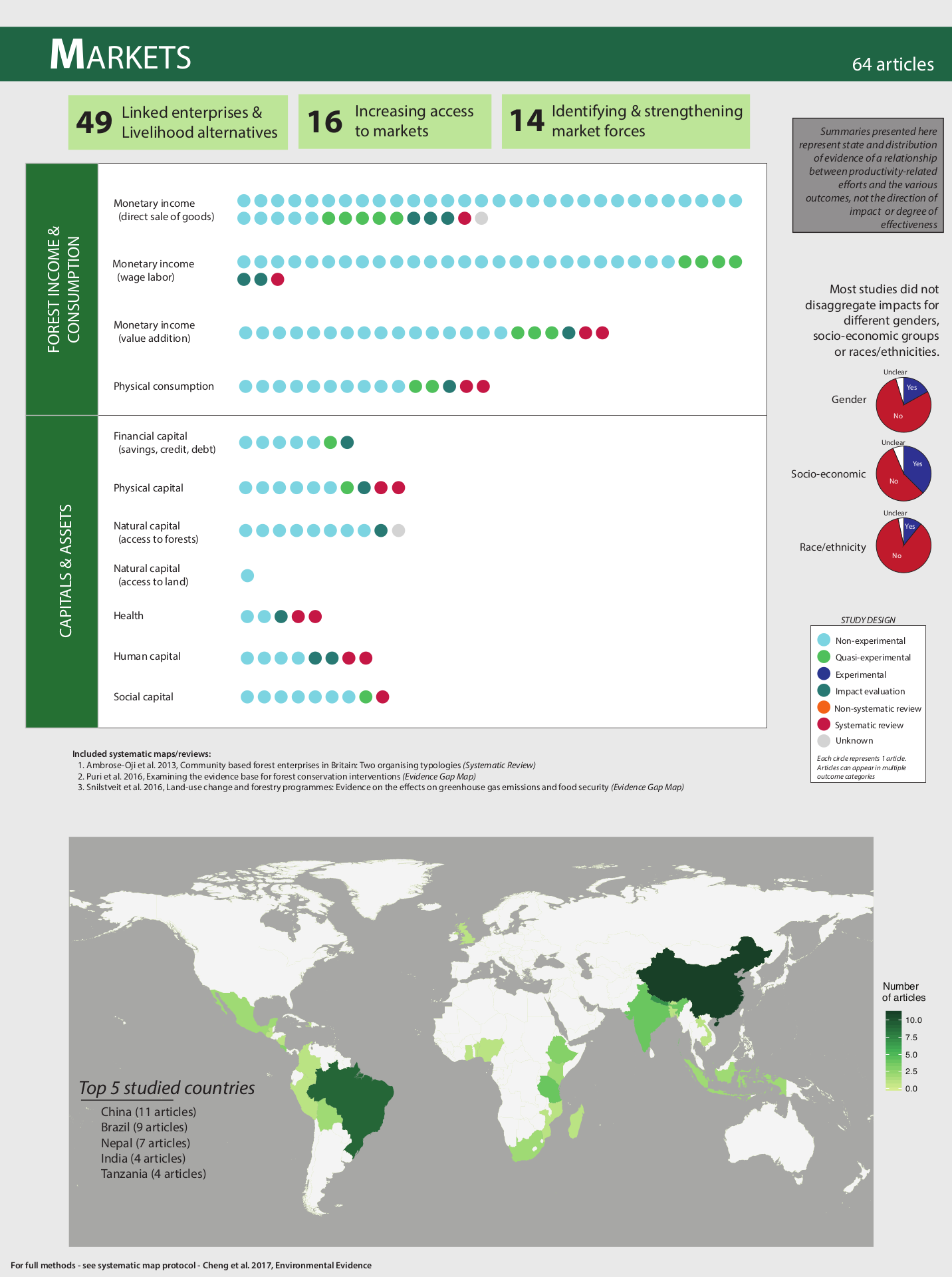

- Evidence map: There is evidence on how increasing market access and strengthening market forces can increase monetary income through direct sales of forest goods and wage labor, but very little evidence on impacts on capital

- Country study: Mexico - experience suggests that there are fundamental benefits to communal forest management, especially through Communal Forest Enterprises

- World Bank Portfolio Review: Market-related interventions were only included in 18 percent of the portfolio sample

Overview

Forest-dependent communities have long used forest resources for subsistence purposes. Some of these resources have found larger markets, increasing rents to households. For instance, markets for a small number of high-value NTFPs (e.g. Brazil or Shea nuts) have significantly benefited both men and women (Colfer et al 2015). Giving continued demand for timber, timber certification and growing access to export markets are additional economic strategies.Recent trends have opened new opportunities within timber markets for poor households: forest certification, local forest management, and technological changes. Greater devolution of forest management to local communities and better governance have enhanced access to timber. In addition, technological changes in the plywood and paper industry and the introduction of portable sawmills have made small-scale producers and plantations more competitive (Angelsen and Wunder 2003; Belcher and Kusters 2004). Certification schemes such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) offer an opportunity to poor forest-dependent households (Rametsteiner and Simula 2003; Romero et al 2013). The area under international forest certification has risen from 14 million ha in 2000 to 438 million ha in 2014 (FAO 2015).

However, participation in certification schemes can be cumbersome for forest-dependent small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (Molnar 2004), unless they band together under community forestry enterprises (CFEs) and receive external support (The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) 2004; Antinori and Bray 2005). CFEs can help address many certification challenges related to the scale, quality and sustainability of timber management and associated transaction costs (Molnar 2004; Wiersum et al 2011; Burivalova et al 2016).

NTFPs, including woodfuels, medicinal plants, bushmeat, nuts, honey etc., play a key role in supporting the incomes of many poor households (Neumann and Hirsch 2000; Belcher et al 2005; Wunder et al 2014). Typically, commercially successful NTFPs have a high value-weight ratio, low levels of product adulteration, a stable resource base and product market, and are produced on areas under state administration (Angelsen and Wunder 2003, Belcher et al 2005). One famous example is Shea butter, Burkina Faso’s third most important national export and a key source of income to poor, often landless, women (Schreckenberg 2004). It contributes up to 40-60% to their income (Tincani 2013) and employs around four million women in trade and processing (Maiga and Kologo 2010). However, the income is often not sufficient to provide a livelihood, partly because NTFPs are spread over large areas and quantity and quality varies over time (Angelsen and Wunder 2003, Belcher et al 2005).

Moreover, a high regulatory burden and weak bargaining power push the poor to operate in local and regional markets that get saturated easily, driving down prices (Schreckenberg 2004). Even when products are sold in larger markets, the latter are typically dominated by monopsonies and exploitative market chains, leaving the poor with only a small share of the final benefits (Rasul et al 2008, Shackleton and Gumbo 2010). One strategy is to expand market access by creating ‘origin’ products. Several forest and wild products have already been proposed or registered under Geographical Indication, an intellectual property recognized by the WTO (Egelyng et al 2016). Such ‘origin’ markets, however, face some of the same challenges encountered by certification schemes.

Wood-based fuels play a critical role in meeting local energy needs with an estimated 12% of the world’s population collecting fuelwood and producing charcoal for their own use (FAO 2014). Commercial wood-based fuel value chains benefit the poorest as they require few skills or technology to enter the market (Angelsen and Wunder 2003) and create employment through small-scale wood collection, charcoal production, transportation, and last-mile retail (World Bank 2011). The charcoal sector in Sub-Saharan Africa alone is estimated to employ seven million people.

While recent trends have opened new opportunities in timber and non-timber markets, new technologies and market opportunities available to the forest-dependent poor also further increase pressure on forests by increasing demand for ‘any tree of any size’ (Angelsen and Wunder 2003, Belcher and Kusters 2004). It will thus be critical to safeguard natural forests and promote other sources of timber, for example through smallholder forest plantations (Angelsen and Wunder 2003) and outgrower schemes with the private sector (Mayers 2000, Desmond and Race 2001). Formalizing woodfuel markets may increase threats on forests (Makonda and Gillah 2007). Sustainability issues would need to be addressed by either sourcing fuelwood and charcoal as a by-product of land clearing, or through tree-planting on farms (Angelsen and Wunder 2003). In all the markets discussed, the poor clearly face challenges in both entering markets and extracting sufficient rent from the sale of forest products. A strategy to surpass some of these barriers is for smallholders to organize themselves into self-governing forest producer organizations (FAO and AgriCord 2012, Macqueen 2013 ). These forest producer organizations offer members political as well as economic services, including lobbying for policy changes, improved access to land and markets, economies of scale, information on prices and quality requirements, capacity building, and better linkages to government institutions, the private sector, financial institutions, development agencies and civil society organizations.

Evidence Map Results

The evidence map reports that 64 articles out of the 242 that focused on actions related to linked enterprises and livelihood alternatives (e.g. sawmills, furniture making; NTFP value addition and sale), to increasing market access (forest entrepreneur networks, credit access), and to strengthening market forces (certification, value chain analyses, and forest funds and taxes). This assessment highlighted evidence between these actions and monetary income through direct sales of forest goods and wage labor, but very little evidence with other types of capital.

Illustrative Country Study

In Mexico, the World Bank has funded a project to encourage communities to organize themselves in community forest enterprises. In Mexico, most of the forested land is owned and managed by indigenous people’s communities (communidades) or groups of formerly landless rural people (ejidos) (Antinori and Rausser 2010).

World Bank Portfolio Review Results

Out of the total number of World Bank projects that met the criteria for inclusion in the portfolio analysis completed under this program (38), 7 (roughly 18%) contained forest markets components as defined by the PRIME framework. These projects also contained other PRIME elements, showing the synergies and complementarities that exist among the components. For example, six of the seven markets projects also contained productivity components; four rights components; all also contained investment components; and four ecosystems components. Geographically, the greatest number of forestry projects that contained market components were in the Bank’s East Asia and Pacific (EAP) region (four projects), followed by Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) regions (two and one respectively). The portfolio analysis completed under this program did not identify forestry projects containing markets components in Europe and Central Asia, Middle-East and North-Africa, and South Asia regions.

Split by

Color by